This is technically not a proper Kindle-licious review, since the only way (as of this writing) that you’ll be reading Leave It to Psmith on the Kindle is if you digitize the book yourself. However, this is the last Psmith book and it’s just not proper to review this series without it. If you desire a downloadable version, you can listen to the Audible.com unabridged audio book on your Kindle.

On to the review proper—

One of my first impressions on reading Leave It to Psmith is that this is Wodehouse in his prime, when he’s no longer trying ((From what you see in the book; Wodehouse is well-known for his thorough revision process)) to find his voice, discover his meter, or figure out Psmith. He now knows Psmith like the back of his hand, it seems, and as such he can not only present the character’s strengths, but also the character’s weaknesses. For the first time in the series, we see a Psmith who is not only vulnerable in the physical sense (we saw that in Psmith, Journalist) but also in the more intimate mindset sense. This may be why Leave It to Psmith is viewed by some as the weakest Psmith book, because he doesn’t come across as a force of nature—he’s “just” a very smart man. But in the sense of handling the personality of Psmith from all angles, Leave It to Psmith is the strongest Psmith book.

And no wonder. This is no longer the early Wodehouse, of boyhood adventures or American flash and daring; this is Wodehouse in his romantic comedy period, when the series he’s well known for these days are setting foot on ground—the Jeeves series, and the Blandings series. Leave It to Psmith is, in fact, a cross-over book between Psmith and Blandings, and is probably the best example of Wodehouse’s transition from his early work to his later work. (Which is also why no review series of the Psmith books can leave this one out.)

A few general things of note:

-

The first chapter is brilliant, because it sets into motion so many small details that will gain consequence and momentum through the rest of the book, and matter highly in the end. These range from characterizations to parts of the scenery almost ignored, but not quite.

-

In fact, Wodehouse does a better job of setting all variables into motion than most mystery writers. Everything that happens in the climax or the ending has had its initial roots set much earlier in the book; by the end of the book, any surprises that leap out at you can be extracted from the first half of the book, with most of the important events having long since had their causes introduced in the first chapter.

-

Wodehouse’s gift with words is in full swing (and his revision process figured out by this point), and just about every sentence is a delight, and no words are wasted. There’s no wonder that many people, on encountering Leave It to Psmith for the first time, end up reading it from start to finish quickly, a result that’s associated more with thrillers than with comedies.

-

Psmith’s role is more balanced in this book, appropriately so because Blandings is Wodehouse’s stage for weaving plot from the interactions of numerous characters. Whenever Psmith in a scene, there’s no doubt that he’s a strong, major character, but he doesn’t overwhelm everybody else.

Now for Psmith himself. We first see his presence in Leave It to Psmith not in person, but as an advertisement he’s put out in the paper:

LEAVE IT TO PSMITH

Psmith Will Help You

Psmith Is Ready For Anything

DO YOU WANT

Someone To Manage Your Affairs?

Someone To Handle Your Business?

Someone To Take The Dog For A Run?

Someone To Assassinate Your Aunt?

PSMITH WILL DO IT

CRIME NOT OBJECTED TO

Whatever Job You Have To Offer

(Provided It Has Nothing To Do With Fish)

LEAVE IT TO PSMITH

Address Applications T “R. Psmith, Box 365”

LEAVE IT TO PSMITH

which certainly sounds like the Psmith we know and love, but the details don’t strike us as all being right in the world.

One of the distinguishing parts of Psmith’s status in the earlier books was: he’s rich, and has a rich family. This allows for strong abilities like the secret buyings of newspapers in Psmith, Journalist, easing Mike’s life of pennilessness and even solving it in Psmith in the City, and of course having been at Eton in Mike and Psmith, and having the familial status to absolve the worst of falls he could have had in all the times he’s shielded Mike. Psmith is secure in a way other people aren’t, and on top of that has a strong and assertive personality.

Wodehouse probably wondered, “what happens if I destroy his wealth?” which just goes to show that it’s unhealthy to be an interesting character to your author.

So at the beginning of Leave It to Psmith, Psmith’s father is dead, the estate bankrupt and bought out, Mike’s secure job as estate manager thrown out by the new buyers, and Psmith himself penniless and working in the fish market for an uncle who, while offscreen, acts similarly to Mr. Bickersdyke in Psmith in the City. Sort of a Psmith nightmare come true. Mike himself has married, and his family is in trouble—and there’s nothing Psmith is able to do to help him this time. Which is, by the way, an interesting part of Psmith’s personality—you’d think that a young man who is otherwise so selfish would never spend so much effort being kind to a person he likes, with more effort than he puts towards himself. And yet that is so very Psmith. It’s also very Psmith to decide to market out that helpfulness to others.

And so, for the first time, we see him uncertain, even about his name, revealed briefly but definitely in his short conversation with the Jackson’s maid at Jackson’s run-down “new” house:

“Ah well,” he said, “we must always remember that these disappointments are sent to us for some good purpose. No doubt they make us more spiritual. Will you inform her that I called? the name is Psmith. P-smith.”

“Peasmith, sir?”

“No, no. P-s-m-i-t-h. I should explain to you that I started life without the initial letter, and my father always clung ruggedly to the plain Smith. But it seemed to me that there were so many Smiths in the world that a little variety might well be introduced. Smythe I look on as a cowardly evasion, nor do I approve of the too prevalent custom of tacking another name on in front by means of a hyphen. So I decided to adopt the Psmith. The p, I should add for your guidance, is silent, as in phthisis, psychic, and ptarmigan. You follow me?”

“Y-yes, sir.”

“You don’t think,” he said anxiously, “that I did wrong in pursuing this course?”

“N-no, sir.”

“Splendid!” said the young man, flicking a speck of dust from his coat-sleeve. “Splendid! Splendid!”

Compare this to his introduction in Mike and Psmith, where he mentions “I’ve decided to strike out a fresh line. I shall found a new dynasty….” It’s telling that the chapters in both works are entitled “Enter Psmith”.

If Psmith is this insecure with a maid (and throughout the book there are mentions where he hopes that the person in a scene will think there’s something special about him, something that’s never been obvious in previous books), I wonder how much it hurt when Mike called him an ass and meant it, which he has never done before in anything but jest. It’s never shown, but we know from the conversation with the maid several paragraphs previous that all is not quite right with Psmith.

In “Enter Psmith” in Leave It to Psmith, we also meet for the first time Eve Halliday, who will play an important role in Psmith’s life. She’s the first woman he ever falls in love with. And he would probably only have fallen in love if he were in this vulnerable state of mind that Wodehouse so thoughtfully plunked him in (I’ll note that it took a lot of doing on Wodehouse’s part to actually effect that in Psmith).

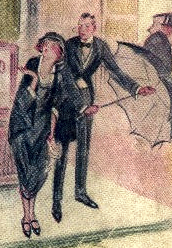

The next chapter, “Eve Borrows an Umbrella”, starts with one of the funniest first-meeting scenes in romantic comedy ever, when Psmith contemplates Eve across the street in the safety of his club, and, seeing that she’s marooned under an awning by an enthusiastic rainfall, thinks

Why, Psmith asked himself, was this? Even, he argued, if Charles the chauffeur had been given the day off or was driving her father the millionaire to the City to attend to his vast interests, she could surely afford a cab-fare? We, who are familiar with the state of Eve’s finances, can understand her inability to take cabs, but Psmith was frankly perplexed.

Being, however, both ready-witted and chivalrous, he perceived that this was no time for idle speculation. His not to reason why; his obvious duty was to take steps to assist Beauty in distress. He left the window of the smoking-room, and, having made his way with a smooth dignity to the club’s cloak-room, proceeded to submit a row of umbrellas to a close inspection. He was not easy to satisfy. Two which he went so far as to pull out of the rack he returned with a shake of the head. Quite good umbrellas, but not fit for this special service. At length, however, he found a beauty, and a gentle smile flickered across his solemn face. He put up his monocle and gazed searchingly at the umbrella. It seemed to answer every test. He was well pleased with it.

“Whose,” he inquired of the attendant, “is this?”

“Belongs to the Honourable Mr. Walderwick, sir.”

“Ah!” said Psmith tolerantly.

He tucked the umbrella under his arm and went out.

We’ll note that (a) Psmith doesn’t have an umbrella to loan Ms. Halliday, but (b) he doesn’t let that stop him, and (c) this is the first time we’ve seen Psmith be Psmith again, and also (d) it’s possible to come up with various metaphors about umbrellas and rain to Psmith’s assistance and the troubles of life. We’ll also additionally note that Psmith has good taste in a life partner, for Eve is not a doormat, nor vain, nor stupid, but a smart and enterprising woman who wants much out of life, not just an enterprising man (which we have no doubt that Psmith is).

After this catalyst, this motivator, Psmith has a purpose again (just as he was bored out of his mind in Mike and Psmith before encountering his protectee, Mike) and the book rolls on even faster forwards than it did before. It’s trivial to say, “Psmith takes a job to steal a necklace at Blandings Castle but also engages in the job at all because Eve is going to Blandings as a librarian, and we end up with several layers of imposter-ship and cross-purposes plotting at Blandings, which is pretty much the purpose of Blandings, and it’s all action and humor from here on out, and also there are flowerpots” but that doesn’t even begin to approach the story. You have to read it (or listen to it).

Everything ends well, eventually, for Psmith, who is finally able to help Mike again, and who also gets the girl (and a job).

And that closes the final chapter on Psmith’s story, although in a foreword to the original Mike and Psmith, Wodehouse notes,

If anyone is curious as to what became of Mike and Psmith in later life, I can supply the facts. Mike, always devoted to country life, ran a prosperous farm. Psmith, inevitably perhaps, became an equally prosperous counselor at the bar like Perry Mason, specializing, like Perry, in appearing for the defense.

For Mike, we learn that it’s most certainly true. For Psmith, we haven’t yet seen it, but I think we shouldn’t doubt it.

Of late, I have thought of this tune as, in some places at least, an appropriate ending track for Psmith, although it’s not for everybody.

Umbrella (excerpt) by Rihanna

Buy track from Amazon mp3 Downloads

/flash/dewplayer.swf?mp3=/wp-content/uploads/under-my-umbrella.mp3&showtime=1

Buy and read Leave It to Psmith:

- Leave It to Psmith, Overlook archive hardcover edition

- Leave It to Psmith, Paperback edition

- Leave It to Psmith, Unabridged Audio Book, downloadable from Audible.com

- Leave It to Psmith, Unabridged Audio Book, CDs

Posts in this series:

Speaking of revisions, the ending in the book of Leave it to Psmith is not the original ending when it was published as a serial in the Saturday Evening Post. The difference is only a couple of hundred words, but I think (in my pretentious way) that the original is better. In the book, Psmith comes out on top through sudden violence (in a good cause); in the magazine, he uses his brain. I suspect he was pressured to change the ending because in the first version Miss Peavey and Ed do make a profit, but it may all have been his idea.

Thanks,

-V.

V,

That alternate ending is quite intriguing. I prefer times when Psmith uses his brain, so I think I would share your opinion.

Now I need to figure out whether my library has or can obtain access to microfiche for the 20’s Saturday Evening Post!

V — also found your post from 2004 on the matter. Neat.